We often think of exercise as something we should do to improve fitness, reach the finish line at a marathon or just tick a box. But in reality movement is smooch more than that.

Movement is what allows you to get up off the floor with your kids. It’s what keeps you independent as you age. It’s what lets you travel, garden, lift, carry, play sport, and say yes to the things you love.

When we talk about movement in clinic, we’re not talking about punishment or extremes. We’re talking about function and longevity.

Movement Is Medicine (But It’s Also Maintenance)

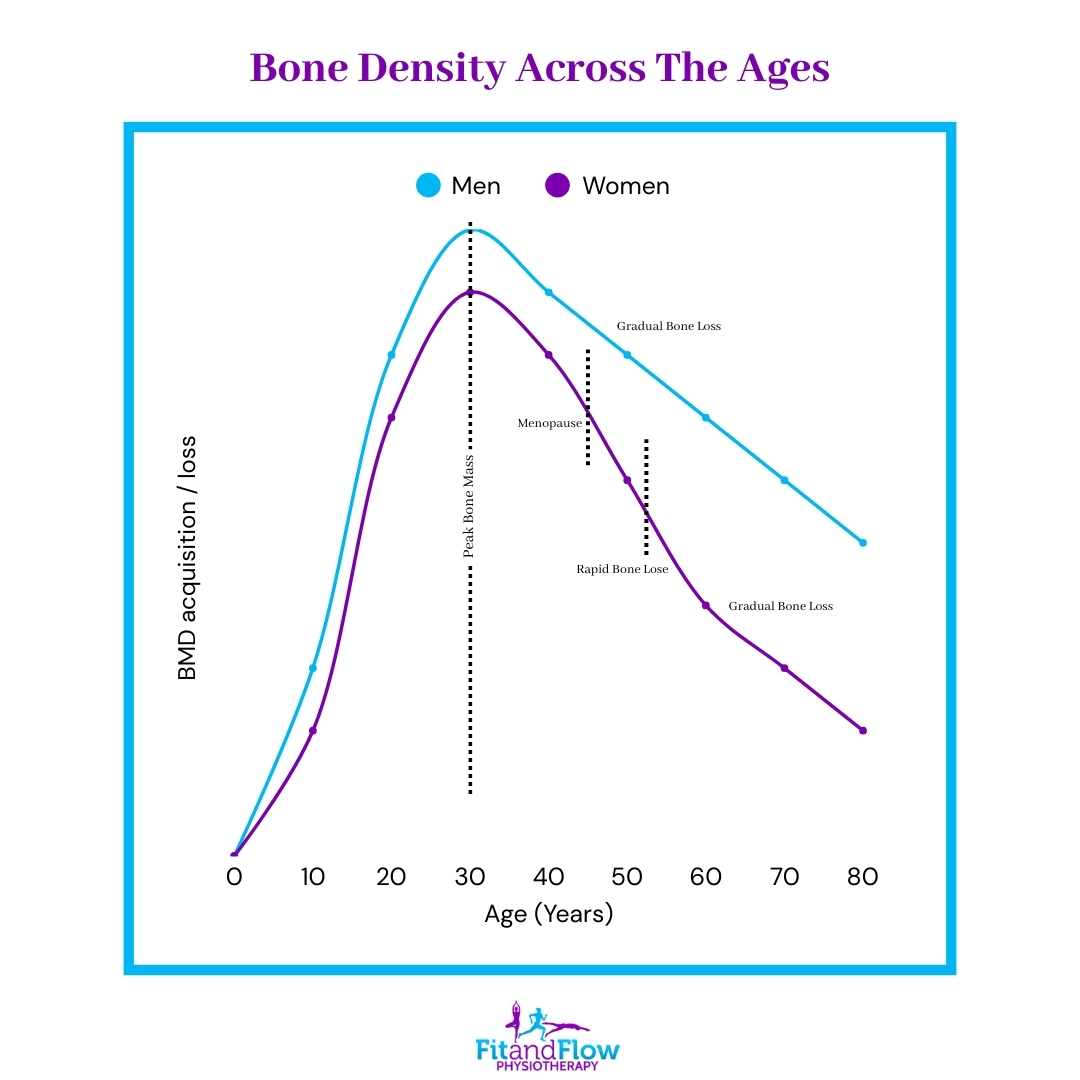

Your body is designed to move. Joints rely on movement to stay nourished. Muscles need load to maintain strength. Bones require resistance to preserve density. Without regular movement, we don’t just lose fitness, we gradually lose capacity. That might mean:

– Feeling stiff getting out of a chair

– Losing confidence when lifting or bending

– Fatigue during everyday activities

– Increased risk of injury

Even subtle declines in strength or balance can impact daily life. The good new? With the right guidance, these are easily preventable and reversible.

WHAT THE RESEARCH SAYS: STRENGTH, BALANCE AND BONE HEALTH

1. Resistance Training Builds Strength and Beyond

Multiple studies show that resistance training (eg. Resistance bands, dumbbells, kettlebells, machine weights etc) significantly improves:

– Muscle strength and joint stability

– Physical performance in daily activities like lifting, bending or climbing stairs

– Bone density, particularly in areas prone to stress or injury

For all adults, resistance training isn’t just about aesthetics, it’s about protecting your body from injury, maintaining mobility and supporting long-term health.

2.Balance Training Improves Coordination & Injury Prevention

Balance isn’t just for older adults. Strong balance and body control reduce the risk of slips, falls, and sports or work related injuries at any age. Evidence shows that balance exercises:

– Improve postural control and coordination

– Enhance reaction times

– Build confidence in dynamic movements like lunging, lifting or twisting

3. The Power of Combining Strength & Balance

Programs that blends resistance, balance, and functional movement are most effective for real-life performance. They help you:

– Move efficiency and safely

– Support joints

– Maintain function and independence

This approach isn’t just preventative, it’s proactive.

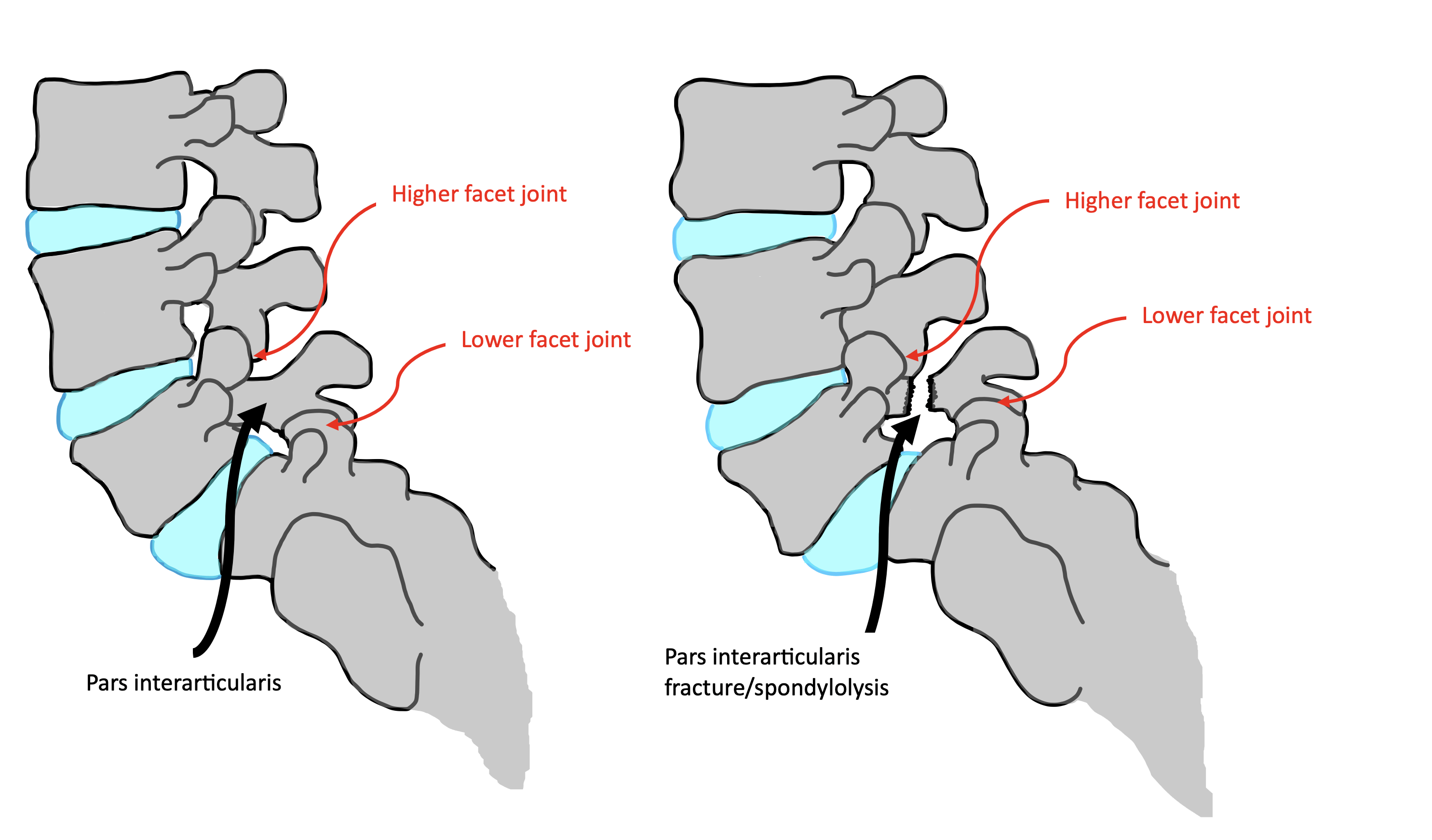

Recovery After Injury

Injury can change the way your body moves. Pain weakness, or stiffness often loads to subtle compensations that increase the risk of further injury.

That’s where physio-led rehab makes a difference:

– To assess your movement and identify weakness or imbalance

– Rebuild strength safely around the affected area

– Correct movement patterns to prevent flare-up

– Create specific exercises that align with your goals

With structured guidance, recovery isn’t just about getting out of pain, it’s about rebuilding function.

The Bigger Picture

Regular movement supports:

– Energy and endurance

– Mental clarity and focus

– Mood and stress regulation

– Confidence in daily life

Your Future Self Will Thank You

Think beyond the next week or month. The movement and strength habits you build now directly impact how capable, confident and resilient you will feel over the next 10, 20, 30 years etc. If you’ve had an injury, or you want guidance on safe, effective movement, structured physic-led programs make all the difference.

Because movement isn’t just about fitness, it’s an investment in your function and quality of life.